Music, Missions, and More

The Mount Carmel Archives of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Mount Carmel in Dubuque, Iowa, are like Fort Knox gold for anyone digging for stories and facts about BVM life during the past 185 years. It was where this writer searched for answers to two related questions:

First: Why and how did BVM piano teachers support the BVM education ministry from 1843 on, as oral history suggests?

Second: How could BVMs build and operate five academies, eight boarding schools, two colleges, two novitiates, and a Motherhouse and a Scholasticate, while simultaneously teaching thousands of children in more than 200 BVM-administered schools scattered across 20 states—and not go bankrupt?

Answers can be found in bulky account books preserved in the archives, and perhaps in the experience of Foundress Mary Frances Clarke and her BVM sisters in 1843 Dubuque.

Dubuque: 1843

A week after arriving in frontier Dubuque, the BVM sisters opened a small boarding school. It did not thrive at first, so they had little to live on. During their first Iowa winter, they were in such straits that they took in sewing and gave piano lessons.

It was obvious the sisters needed more than tuition to support themselves. As membership increased, and Mary Frances sent BVMs to open parish schools beyond Dubuque, the group often included at least two classroom teachers, a housekeeper, and a piano teacher.

Mary Frances also devised a practical way for the sisters to handle the monies they received: “Use what you need, and send in the rest” (to the Motherhouse). That “rule” has guided BVMs ever since.

Why Piano Teachers?

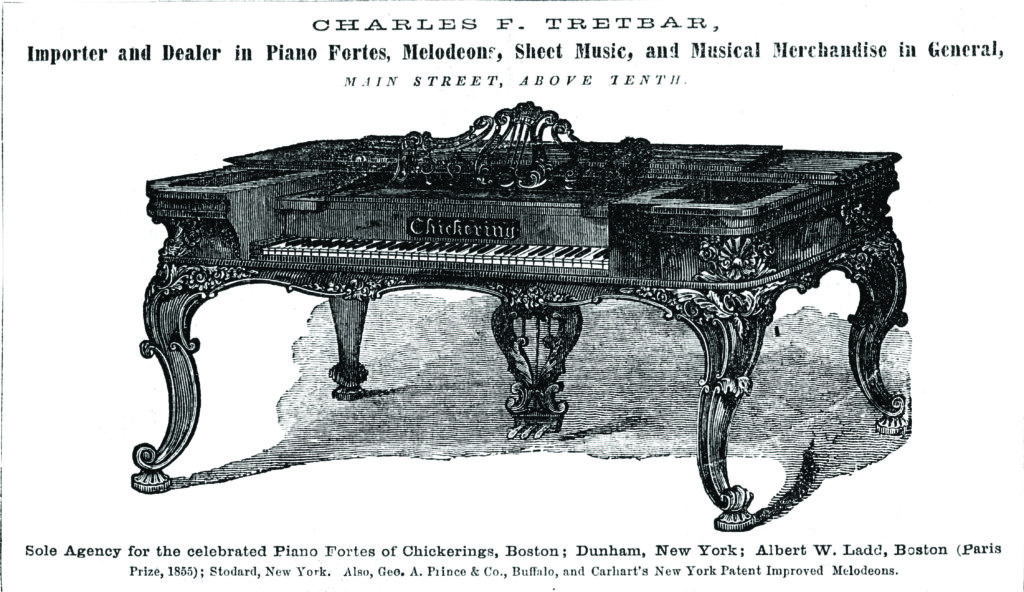

The piano became popular and affordable during the early 1800s. Dozens of competing piano factories sprang up in Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Chicago. Their goal: a piano in every parlor, school, theatre, and saloon. Pianos became social equalizers and entertainment centers. People clamored for piano teachers.

Accomplished pianists had become BVMs in Philadelphia; now they became piano teachers. Four hundred more BVM pianists did the same. When pastors couldn’t or wouldn’t pay the full salary to classroom teachers, the sisters could neither make ends meet nor send money to support the Motherhouse in Dubuque. The lessons money, however, could erase the convent deficit and provide some extra to “send in.” It became a cushion against hard times.

The money sent to Dubuque could be moved to wherever it was needed. The Motherhouse was supported, needy convents received help, buildings could be built, and the ministry continue.

Other religious communities also relied on piano lessons to balance their budgets; BVMs were not alone.

Accounting for the Money

Struggles to balance budgets show up in the 239 account books (ledgers) written between 1843 and 1994, and preserved in the Mount Carmel Archives. Fewer than half of the nearly 200 schools staffed by BVMs have account books there. That was not a major problem because between 1893 and 1955, nearly every convent sent six-month and 12-month reports to Mount Carmel. These were summarized and copied into five “Mission Receipts and Expenses.”

Identically arranged categories (line items) were used for BVM accounts. Entries were written in ink into multi-year ledgers. “Salaries” is the first item on the Receipts page; “Piano” is the second.

These meticulously kept account books contain more than numbers. They hold BVM histories, compressed between two covers.

What the Numbers Show

Four uncomplicated account categories were chosen for examination for this article: Salary and Piano Incomes, and Living Expenses and Remittances (money sent to support the congregation).

Data from accounts of 45 randomly selected large and small parish schools from across the United States, operating between 1890 and 1961, were entered into a dozen spreadsheets and analyzed in various ways.

Here is an example from the decade after the death of Mary Frances Clarke (1887). It shows that the decision she made in 1844, to use piano lessons income to support the congregation, worked. The same process and success continued until cassette tapes and recordings lowered the need for a piano in every parlor, and music teachers found new ways to use their skills.

Data from 1894 and 1899, from accounts of seven (7) convents from California, Iowa, Illinois, and Kansas.

Two years’ worth of data from each convent are combined. Together they had expenses of $19,988, but salaries totaled only $14,387. Ideally, the salaries would have covered expenses with money left over to send in to Mount Carmel. Instead, they were $5,601 in the red.

However, they had $3,088 from other income sources (gifts, sales of pencils, etc.), plus the piano lessons income of $8,689. By taking $2,513 from the piano lessons income, and adding that to the other income sources, they not only erased their deficit and ended up in the black, but they had $6,569 left to remit for congregational support. Without the piano lessons income, they would have had nothing to remit and a deficit of $2,513. (Sound small? The deficit’s equivalent in 2017 dollars is about $63,000.)

During the 1930s, 100 percent of the lessons income was usually remitted, along with every extra dime the sisters could earn and spare, for the congregation had much debt from loans incurred during the previous 20 years. Realmo Sullivan, BVM—treasurer from 1925–55—using loans, bonds, mortgages, and sophisticated juggling, managed to keep the congregation afloat.

Source: Center for Dubuque History, Loras College

Lessons Provide Cushion

For nearly 140 years, more than 400 BVM piano teachers made a significant contribution to the common purse of the congregation by teaching piano lessons. Without the piano “cushion money,” it would have been more difficult to financially support congregational administration, new members, and the sick and aging, or to undertake needed building projects, continue sisters’ education, establish special missions, and most importantly, reduce debt, for debts were seemingly without end.

Every BVM helped achieve those goals. Generous benefactors, from 1833 on, have added their support. Prayer accomplished miracles. So did individuals such as Realmo Sullivan, who inscribed in her accounts: “God giveth the increase.”

So in spite of debts, mortgages, and multitudinous loans, bankruptcy did not result; the BVMs and their ministry of education continued without interruption for 185 years.

BVM piano teachers played a unique role in making this happen; the account books document it. But Mary Frances Clarke made it possible with the simple but challenging guide: “Use what you need, and send in the rest.”

About the author: Bertha Fox, BVM (Dolorose) served on the faculty of Clarke University in Dubuque, Iowa, as music teacher and music department chair. She is retired and lives at Mount Carmel, Dubuque.

This story was featured in:

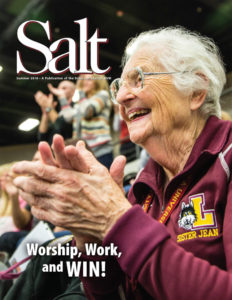

Summer Salt 2018: Worship, Work, and WIN!

Summer Salt 2018: Worship, Work, and WIN!

Win or lose, the Loyola University Chicago Ramblers know they can count on the love and support of their 98-years-young chaplain, Sister Jean Dolores Schmidt, BVM. This year’s NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament (a.k.a March Madness) propelled Sister Jean and her team to the Final Four—and gave the world a chance to see BVM values in action. Read more about Sister Jean and the BVM Legacy of Love.

If you would like to receive Salt, contact the Office of Development for a complimentary subscription at development@bvmcong.org or 563-585-2864.