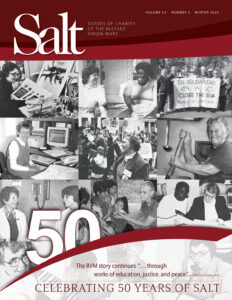

Salt: 50 Years of Evolving Ministry

In 1982, a group of 66 BVMs chartered a bus and went to New York City to peacefully protest the nuclear arms race.

The Second Article of a Three-Part Series

by Teri Hadro, BVM

Salt magazine is half a century old! For 50 years it has brought to life the story of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, bridging past and present, giving members and associates, donors, family, and friends glimpses of the unfolding landscape.

Perhaps the most unexpected and global change for the congregation was the evolution of its ministerial outreach. Two years after the landmark Chapter of 1968, which implemented the changes of Vatican II, and four years before the first issue of Salt, the 1970 BVM Senate passed a transformative piece of legislation called Totally Open Personnel Application (TOPA) allowing sisters to pursue individual ministries.

Over the next two decades and beyond, Salt magazine chronicled the impact on BVM ministry. A congregation whose members had served, almost exclusively, as classroom educators for 137 years evolved into a group of dedicated women who, with boldness and imagination, began to realize the commitments captured in the 1984 revision of the BVM Constitutions: “Compelled by the example and word of Mary Frances Clarke in her sensitive response to critical human situations, we strive to seek out and attend to those in need whatever this may require of us.” And, “We are called to live in any part of the world where there is promise of furthering the mission of Jesus through works of education, justice, and peace.”

Expanded Consciousness

In 1970, the BVM Senate agreed that “[a]s witness to the redeeming presence of Christ in the world, the congregation continues to give priority to the field of education while at the same time admitting of diversity of service . . . We recommend that sisters be free to determine their own areas of service.”

Open Application meant that there no longer would be numerical restrictions or quotas for schools in which BVMs taught, but sisters soon realized that witnessing to the presence of the redeeming Christ extended well beyond the classroom.

They also appreciated that education, a critical component of healthy human development, went far beyond academics. Witnessing to the redeeming presence of Christ in the world became the raison d’etre for ministry discernment for most BVMs. They turned their attention to “seeking out and attending to those in need” by learning about and responding to the signs of the times.

Seismic Changes

The results were seismic! Over 50 years, areas of BVM ministry have included religious education, parish administration, retreat design and facilitation, spiritual direction, communion ministry, and pastoral and hospice care. BVMs have been parish liturgists and musicians, vicars for religious, school administrators, and superintendents. BVM artists were free to develop their crafts—painting, sculpting, music therapy, and poetry to name just a few.

BVMs took over and rejuvenated struggling schools, served in schools run by other congregations, dioceses, and state university systems. They’ve been sports coaches, team tutors and chaplains, taught in seminaries, assisted fledgling congregations of women religious in developing nations, and went to jail with nonviolent actions for justice. Authors of Salt articles were with them every step of the way.

As new societal needs emerged, BVMs frequently were found among the pioneers—HIV/AIDS ministries, chemical dependency counseling, genetic counseling, and more. BVMs learned they had transferrable skills as they administered senior living communities, programs for children with special needs, and joined colleagues at Catholic Charities-sponsored centers for the poor, for migrants, for the unhoused.

Growing Global Consciousness

With the formation of geopolitical movements, BVMs were found serving as legal counsel for whistleblowers, standing with farm workers, teaching English as a second language, advocating for women’s rights at the United Nations, for closure of the School of the Americas, for the abolition of capital punishment, for comprehensive immigration reform, against violence in any form, for preservation of Earth and all creation, and against human trafficking.

In the very first issue, Salt’s editors predicted: “For BVMs, engaging in new ministries is just a beginning. Increased personal freedom and fuller participation in today’s world will continue to challenge women religious to new expressions of their awareness of oppression, their recognition of demands for as-yet-uncreated ministries, and their expanded understanding of church and the brotherhood of Jesus.” And the editors re-stated Salt’s purpose: “In reporting and interpreting these people-issues, Salt will be a bridge to the future.” TOPA was just the beginning. When BVMs read the signs of the times and joined/founded new ministries, small groups of BVMs formed intentional communities, most often in apartments but in convents as well. This expression of the congregation’s commitment to healthy personal growth and development soon evolved into larger models of collaboration.

The 8th Day Center in Chicago brought seven congregations of women and men together to work for justice; Opening Doors, a residential program for women in crisis was founded by the five religious women’s congregations in Dubuque, Iowa; the Hispanic Ministry Institute and The Gannon Center for Women in Leadership were established at Loyola University in Chicago; ministry sites in Texas, Iowa, and Chicago were opened.

TOPA enabled the BVM world to keep growing. BVMs had been ministering at the Working Boys Center in Quito, Ecuador, since 1967, but no one then envisioned that they would expand their efforts to include teaching underprivileged children at Nuevo Mundo school and founding a residential program for sufferers of Hansen’s disease (leprosy). Salt captured it all as the decades flew by. It also recorded the stories of BVMs serving in Ghana, Guatemala, Japan, India, Hungary, Columbia, and Nicaragua.

New Collaborations

TOPA brought BVMs out of the classroom and into the world. They began to see themselves as agents of change no longer circumscribed by school and parish boundaries. Causes addressing issues bigger than any one local community could speak to drew BVMs to ever larger, collaborative and interdependent groups.

Racism, sexism, globalization, human trafficking, the farm worker movement, Alzheimer’s disease, extreme poverty, climate change, gun control, and more drew them to marches, protests, planning sessions, and board memberships.

No area of the human sphere was excluded from the need for them to witness to the “redeeming presence of Christ.”

Their ministerial evolution enabled BVMs, previously celebrated as outstanding educators in their own schools, to become women more deeply engaged with each other and with the women and men with whom they walk, work, plan, and address the human needs of others. Salt’s reporters, editors, and production teams have kept pace.

The BVM story continues.

Related:

What’s in a Name?

What’s in a Name?

by Teri Hadro

Around 10 a.m. one Saturday morning in 1974 about a dozen BVMs with communications backgrounds gathered at Wright Hall, a BVM residence in Chicago, to name the new magazine. Not a complicated task, but given the talent and experience in the room, one might have expected diverse opinions.

Within 20 minutes, the blackboard was covered with 30+ possible names. We didn’t have cellphones in those days, so no digital snapshot was taken. The only name other than Salt that I can remember was “Cellar Door,” suggested by a veteran English teacher and deemed “the most euphonious phrase in the English language.”

Conversation was brisk, sometimes contentious, sometimes educational, and by noon the group broke for lunch with the

30+ suggestions still intact.

When the group reconvened, a new tack was pursued. We’d eliminate non-contenders. It took an hour, but we were down to about a dozen possibilities. As the projected meeting’s end approached, participants were getting restless. I’d use the word “desperate,” but we were having too much fun and enjoying each other’s company.

Finally at 2:55 p.m. editor Rita Benz, BVM put her foot down, “We need a name!” It was not unanimous, but Salt gathered a majority of votes, and the successor to Vista was christened. The name was short, sweet, and biblical.

We hired graphic artist Gene Tarpey to design the format, and he never asked what Salt meant—which was good since no one actually knew. He went with salt as a flavor enhancer and added regular features Accent (President’s message), Seasonings (notes from editors or leadership) and A Pinch of Pepper (op-eds, mostly by Kathryn Lawlor, BVM). The Salt logo had round grains sprinkled over the letters. Tarpey’s format stuck because by then the editors had turned their attention to content.

Salt’s intent in 1974 and to this day, is to tell the BVM story as the sisters live it. For 50 years, the magazine has done just that. Salt has chronicled ministerial and organizational changes, growth in spirituality, lifestyle changes, and much more. What has remained clear is that BVMs and associates haven’t lost the savor inspired by Foundress Mary Frances Clarke. Fifty years of Salt covers testify we are among the “salt of the earth!”

This story was featured in:

Winter 2025: Celebrating 50 Years of Salt

If you would like to receive Salt, contact the Office of Development for a complimentary subscription at development@bvmsisters.org or 563-585-2864.