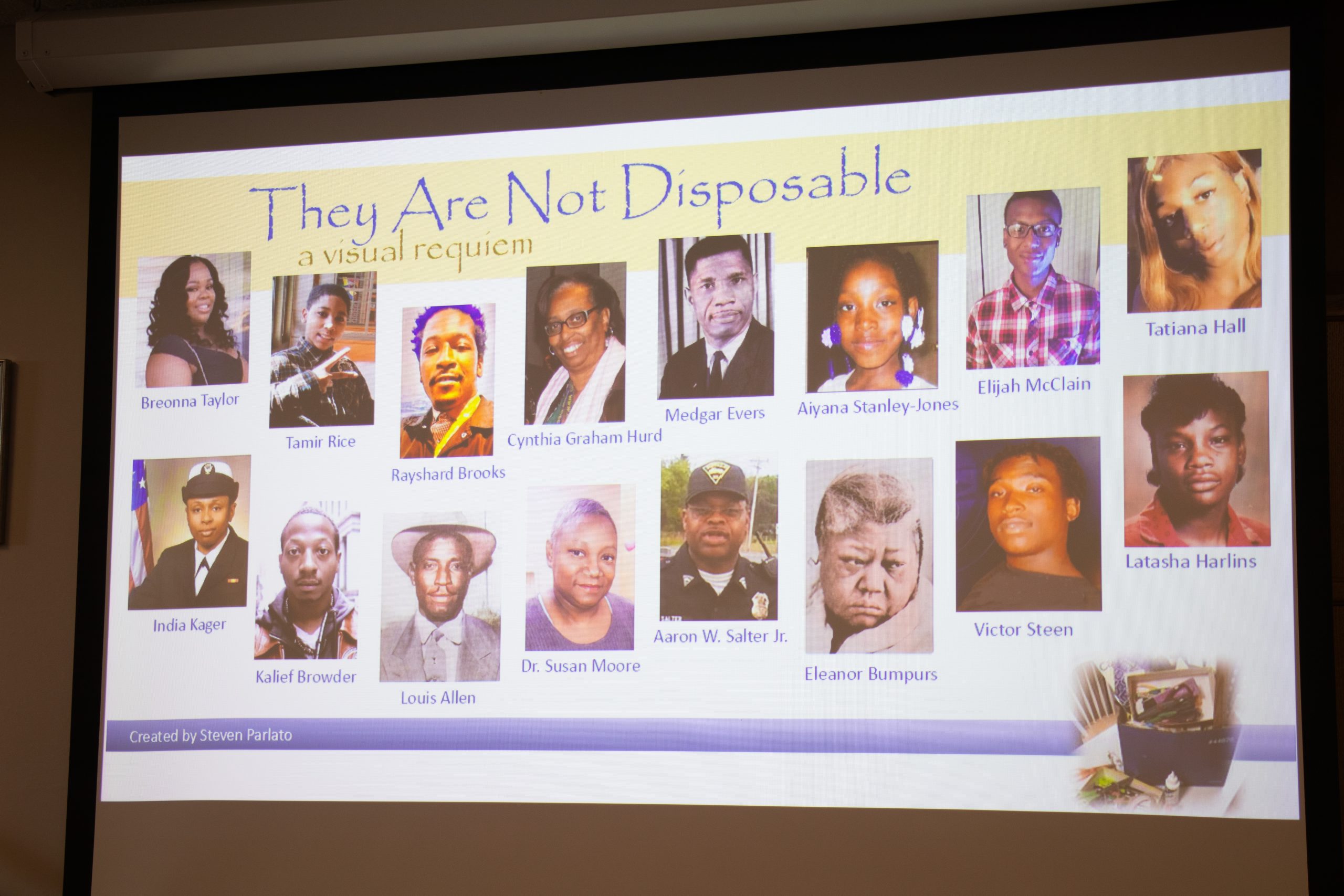

At Voices Studios: ‘They Are Not Disposable’ Exhibit Brings Systemic Racism Out of the Dark

BVM Sisters recently welcomed Connecticut-based artist Steven Parlato for an in-person presentation about his Voices Studios exhibit, “They Are Not Disposable.”

Sisters of Charity, BVM, Sisters of the Presentation, and the Dubuque Franciscans, all of whom have a strong commitment to racial justice, were instrumental in bringing Steven and his work to Dubuque, Iowa.

Theresa Caluori, BVM was appreciative of the artist’s visit to Mount Carmel.

“I loved the progression that he showed as to how he worked and the research that he did on each person to really reflect who that person was,” she says.

“They Are Not Disposable” depicts 16 Black Americans whose lives were cut short by systemic racism and racial violence, from civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who was killed in his own driveway in Jackson, Miss. in 1963, to Aaron Salter Jr., a retired Buffalo, N.Y. police lieutenant who was one of 10 victims in the Tops Supermarket mass shooting in 2022.

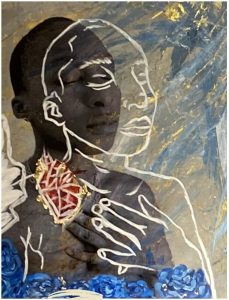

“I had all this junk,” Steven says. “Breonna Taylor had been killed. And then George Floyd. It was June 5, [2020] and it was Breonna’s birthday, and I just felt I had to do something, so I created this portrait of her.”

Steven created five more portraits that year, looking specifically for Black Americans who had lost their lives for reasons related to their race. He also wrote poems to accompany each piece.

“I had so many different feelings doing this work,” he says. “I almost felt like a vulture circling looking for subjects.”

The collage portraits were created using “junk” that he had collected for a poetry project—junk mail, paper bags, to go containers, wrapping paper, straws, used dryer sheets, and lots more.

It took Steven three years to complete all the portraits. How the collection came to Dubuque from his home in Connecticut certainly seems like a divine happening.

The portraits were being exhibited at Mercy by the Sea Retreat Center in Madison, Conn., where they were seen by a visitor from Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia, who contacted Steven after she returned home. He was asked to present the collection via Zoom for a session of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. Dubuque Franciscan Associate Dave Heiar saw a recording of that session.

“I was determined that we were going to get Steven to come here and bring his art,” Dave says.

Working with some of the women religious in Dubuque, whose commitment to social justice is strong, as well as Voices Studios, a gallery and exhibit space that often celebrates Black artists in the community, Dave soon had a plan for bringing Steven and his artwork to the area.

“Without Dave, none of this would have happened,” Steven says.

It was also a boost of confidence for the artist, who had three collages from the collection stolen while they were on display at a library near his home this past spring. He spent most of the summer recreating them.

“I just couldn’t let them be erased twice,” he says.

The exhibit opened on Aug. 1 at Voices Studios and will be on display through Saturday, Sept. 20. It is the centerpiece of a series of events that will take place through mid-September.

Theresa has viewed the powerfully emotional exhibit in person.

“I was really grateful that I heard him talk before I viewed the art,” she says. “It made it much more personal. It really brought me to another level when I was looking at the pieces.”

Local Black artists Will Pearsall, Marley Washington, Rhonda Bees, and Madison Rhymes will have their work featured alongside “They Are Not Disposable.” Other events highlight talented Black artists in several mediums, including film, spoken word, music and fashion. There will also be a moderated panel on Black enterprise, and a memorial event honoring Nathaniel Morgan, one of Dubuque’s first residents.

For more information on “They Are Not Disposable” and other events being held in conjunction with the exhibit, visit voicesstudios.org.

Remembering Nathaniel Morgan

Theresa and fellow BVM Sara McAlpin joined the Nathaniel Morgan Memorial Committee in 2019, a year after it was founded. Sara passed away in 2024. Theresa continues to work with the committee.

“It’s a committee that has struggled, but now things are happening,” she says. “2028 is our goal [to have the memorial in place].”

Nathaniel moved to Dubuque from Galena, Ill. in 1830 with his wife, Charlotte. They were free persons of color. Nathaniel was one of the first members of the community, Black or White, to buy a city lot. He and Charlotte built their home on “Lot Number One,” near 1st and Main streets. Nathaniel, a porter at a hotel, was a founding member, along with Charlotte, of the first church in Iowa, a Methodist church near Washington Park.

One day, a guest at the hotel, which was located where Hotel Julien Dubuque now stands, couldn’t find his suitcase. He assumed the Black porter must have taken it, and Nathaniel was chased through the city by a local mob that beat him, breaking his back and caving in his rib cage. He did not survive. The leader of the mob was acquitted because he claimed they had not intended to kill Nathaniel.

The committee’s goal is to raise awareness of what was a grossly underacknowledged act of racial violence in Dubuque, and to raise money to create a memorial in Nathanial’s honor.

“Nathaniel not only lost his life,” she says. “But Charlotte Morgan lost her house, her livelihood, she lost everything.”

The committee has raised funds through donations and fundraisers. It is currently accepting proposals from artists, and the Dubuque Museum of Art has donated the space where the memorial will be installed.

If you’d like to know how you can get involved with the Nathaniel Morgan Memorial Committee or other ways you can help, visit facebook.com/p/Nathaniel-Morgan-Memorial-100069221734206.

Everyone has a Story to Tell

While there is no way to measure the number of people whose lives have been taken due to racial violence, discrimination, systemic abuse or prejudices through history, there is one thing we do know—it continues to happen over and over again.

“We know this country has a history of racism,” artist Steven Parlato says. “It’s a terrible constant.”

While the pieces used to create these works of art are disposable, the people depicted in them are not. And they all have a story to tell.

Breonna Taylor, 26, a former EMT who was working as a nurse, was shot and killed during the execution of a no-knock warrant on March 13, 2020 in Louisville, Ky. Police suspected her ex-boyfriend was using her address to receive drug packages, although the USPS said they found no evidence that proved that.

Louis Allen, 44, was an African-American logger who was shot and killed on his land in Liberty, Miss. on Jan. 31, 1964. No one was ever prosecuted for the murder, but the local sheriff, who had harassed Louis repeatedly, was strongly suspected. Louis was killed the day before he had planned to move out of state.

Aiyana Stanley-Jones, 7, was killed by a Detroit police officer on May 16, 2010 during a raid on an apartment one floor above where Aiyana and her family lived. An officer came through the wrong door, shooting Aiyana as she lay on her grandmother’s couch. He was charged, but after two hung juries, the charge was reduced to reckless use of a firearm.

Cynthia Graham Hurd, 54, was a librarian killed in an anti-black mass shooting on June 17, 2015 at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C. Eight others were also killed. The group was meeting for a Bible study. The shooter had joined the group a few weeks before with a pre-meditated plan for murder.

Kalief Browder, 22, was held without trial at Rikers Island in New York for three years on a robbery charge, spending 700 days in solitary confinement. He maintained his innocence. After his release, he suffered from brain health issues that led him to take his own life on June 6, 2015.

Latasha Harlins, 15, was shot and killed on March 16, 1991 by a convenience store owner who thought, incorrectly, that she was stealing a bottle of orange juice. Her killer received a suspended sentence, five years of probation and 400 hours of community service.

India Kager, 27, a Navy veteran, was shot and killed by police who were tailing the car of her and her boyfriend in Virginia Beach, Va. on Sept. 5, 2015 They fired more than 30 rounds. Their four-month-old son, who also was in the car, was miraculously unharmed.

Victor Damarius Steen, 17, was killed on Nov. 12, 1991 when he was struck by a Pensacola, Fla. police cruiser while on his bicycle. The officer had attempted to fire his taser at Victor while he was driving, bringing him close enough to Victor and his bicycle to hit him. Victor’s death led to several changes in how police pursuits are now carried out in the city and how tasers are deployed by law enforcement officers.

Eleanor Bumpurs, 66, was killed by New York City police on Oct. 29, 1984 as they arrived to evict her from her public housing apartment. Eleanor was known to have mental health issues, and the city’s Social Services administration was criticized for how it handled her case.

Susan Moore, 52, was a family practice physician in Carmel, Ind. who died of COVID-19 on Dec. 20, 2020. In the weeks leading up to her death, Susan voiced her concerns that she was experiencing medical racism, and that her illness was not taken seriously by White doctors.

Medgar Evers, 37, a civil rights activist and U.S. Army veteran, was murdered in the driveway of his home in Jackson, Miss. by a member of the White Citizens Council on June 12, 1963. His murderer was finally brought to justice in 1994 and sentenced to life.

Aaron Salter Jr., 55, was a retired Buffalo, N.Y. police lieutenant working as a security guard at Tops Friendly Market. On May 14, 2022, a gunman wearing tactical gear and armed with an assault rifle entered the store. Aaron confronted the attacker and fired multiple shots. He was killed by return fire. It was determined that his acts slowed down the assault and allowed others to get to safety. Aaron was one of 10 people killed by a self-described ethnonationalist. All the victims were Black.

Tatiana Hall, 22, was a transgender woman whose body was discovered on June 29, 2020 in Philadelphia. The coroner recorded her death as “due to drug use and accidental,” but friends and family say drugs were not a part of her world and they suspected foul play.

Tamir Rice, 12, was killed in Cleveland, Ohio on Nov. 22, 2014 by a police officer at a city park. Tamir had a toy gun and was shot a few seconds after police arrived to investigate a citizen’s call, which included information that Tamir was a juvenile and that the gun was “probably fake.” That information was never relayed to the responding officers. The officers were never charged, and it was discovered that one of them had been deemed “emotionally unstable and unfit for duty” by the department where he was previously employed. CPD never investigated his previous employment before hiring him.

Elijah McClain, 23, a massage therapist who was described as “a gentle soul,” was stopped by Aurora, Colo. police officers investigating a suspicious person call. He was put in a carotid chokehold, which resulted in officers calling paramedics, who administered an excessive dose of ketamine on site. Elijah died on Aug. 30, 2019, six days after the incident. Three officers and two paramedics were charged with Elijah’s death. Two officers were acquitted, and none of those who were convicted served more than five years.

Rayshard Brooks, 27, was killed in Atlanta on June 12, 2020 by a police officer who was investigating a drunk driving complaint at a Wendy’s drive-thru. A physical confrontation took place, which resulted in the officer firing three shots, two of which struck Rayshard. Charges of felony murder were brought against the officer, but those charges were later dropped. The incident resulted in the resignation of Atlanta’s police chief. The officer who shot Rayshard was fired, then later reinstated.